The Big Shift

Marketing has reached a turning point: either it abandons the brand building model first invented nearly a century ago, or almost certainly fall victim to the forces of disruption. While no one knows what a next generation planning model looks like, everyone agrees it will take a big shift in thinking to get right.

“Because I think it may be of some help to you in putting through our recommendation for additional men for the Promotion Department I am outlining briefly below the duties of the brand men.”

N. H. McElroy

May 13th, 1931

His 3-page memo became legendary.

It ignited a revolution in marketing that changed the way brands were managed. Written by a junior Proctor & Gamble promotion manager by the name of Neil McElroy, the memo drew attention to the lack of corporate support for products other than the flagship brand Ivory. McElroy proposed a new organizational model that would put dedicated marketing teams in charge of each brand – what McElroy referred to as “brand men”. Overseeing all brand planning, they would “study product shipments”; “examine carefully the combination of effort that seems to be clicking”; “study the past advertising and promotional history of the brand”; and prepare all “necessary material for carrying out the plan”.

His recommendation gave birth to brand management as we know it today. And it helped P&G become the heavyweight champion in consumer good manufacturing. The P&G formula for brand domination: “Find out what consumers want – and give it to them”. P&G also pioneered the heavy use of mass media – initially, radio “soap” operas, later daytime TV commercials – to make their brands recognizable household names.

Most companies eventually adopted the P&G planning model: start by segmenting markets according to demographics, attitudes or usage – find a product solution for a latent or niche consumer need, identified through market research – differentiate through brand positioning – and build top-of-funnel market awareness through mass media campaigns. The marketing planning model behind that process has remained largely the same ever since. As Forrester Research points out in a recent report, “Despite the drumbeat of inexorable change, marketing planning remains stubbornly old school. Most approaches to planning were created in and for a different age; they linger as a vestige of TV and paid media.”

Mark Pritchard, the Chief Brand Officer for Proctor & Gamble, apparently agrees. Speaking at Cannes this past June, he warned, “Mass disruption is the biggest challenge facing the marketing industry today”, adding that “Brands must completely reinvent in order to survive.” Looking to the future, he said, “We’re reinventing marketing to be a force for good and a force for growth.”

Why has P&G suddenly become an advocate of marketing transformation? Mainly due to time-starved connected consumers with negligible attention spans who have zero tolerance for commercial interruptions. In short, wasted ad dollars. Last year P&G slashed its digital spending by $200 million because of what Pritchard calls digital media waste. P&G is now determined to shift from “mass blast” to “one-to-one marketing”, ending the ‘Mad Men” era. “This new transition to one-to-one marketing is going to be a big shift”, Pritchard admits. A Big Shift because no one – not even P&G – has figured out what a next generation planning model looks like.

Keeping up with the Joneses

When McElroy wrote his memo, companies worried mainly about getting the distribution channel to carry their products. At the time, marketing was a lower echelon function, doing the bidding of sales. Their main job was to make and buy ads. But as the practice of brand management matured, marketing grew in stature and credibility, especially in the immediate post-war period, when a pent-up demand for consumer goods was unleashed through mass advertising. For better or worse, marketing served as an unwitting agent of social change: “Buy now, pay later” became a way of life. A burgeoning middle class, feeling affluent, buoyant and acquisitive took advantage of easy credit to live the dream – or at least the dream as portrayed by advertisers: a big house in the suburbs, a fancy car, the latest material comforts. Brand advertising made “Keeping up with the Joneses” a social norm – “conspicuous consumption” a sign of social status.

For better or worse, marketing served as an unwitting agent of social change: ‘Buy now, pay later’ became a way of life.

As consumer product demand accelerated, the purview of marketing expanded. Brand marketers took the lead in identifying target markets, working out pricing tactics, figuring out channel strategy, estimating product demand and streamlining the flow of goods from production lines to the distribution network. Proven methods and practices were codified in academic literature, marked by the publication of books such as Jerome McCarthy’s “Basic Marketing: A Managerial Approach” in 1960 which introduced the concept of the 4Ps, and Philip Kotler’s “Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning and Control”, published in 1967, which stressed the importance of generating “pull” demand. By the end of the 1960s the elements of the classical marketing model were pretty much in place, and they remained that way through the next decade or so.

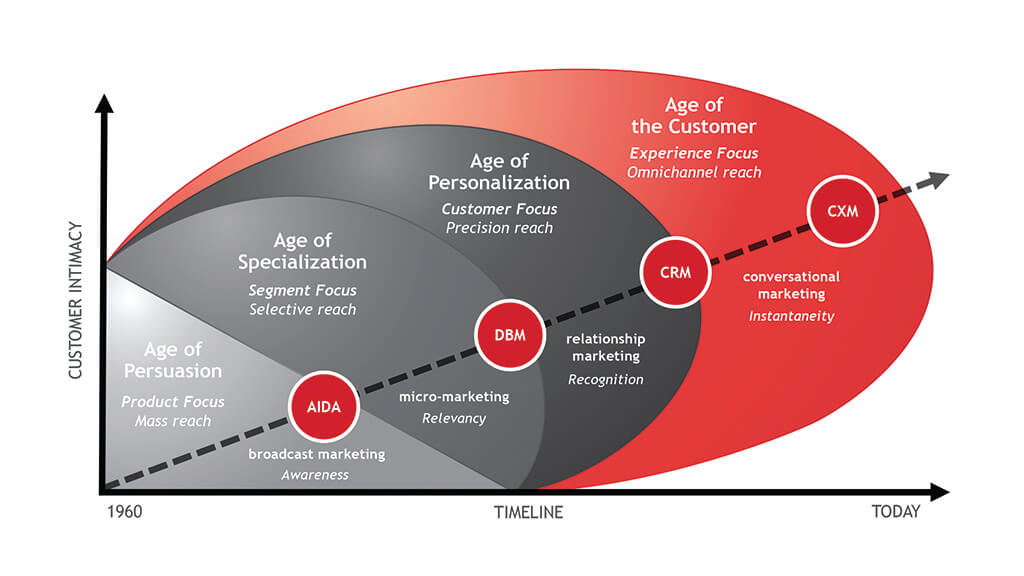

The Rise of CRM

By the 1980s, however, that model was showing signs of wear and tear. For one thing, there was a growing infatuation with addressable media, in part because PC-based technology made it affordable to reach customers directly through mail and outbound telemarketing. Up until that time database marketing was limited to continuity publishers and catalogue companies whose direct-to-consumer model justified the higher media cost-per-order. With the rise of personalization technology, marked by the arrival of high volume digital imaging systems powered by new relational databases, data-driven marketing became popular with banks, credit card marketers, retailers, the gaming business and every other industry that could link purchase transactions to customers.

Around this same time the rapid spread of cable TV had drawn audiences away from the broadcast networks. Mass media was beginning to lose its appeal. An increasing share of the A&P budget began to seep “below the line” into direct marketing. As media fragmentation intensified, the idea of “integrated marketing” came into vogue, promising to optimize the media mix according to relative sales contribution.

When CRM systems appeared in the early 1990s, it became that much easier to collect customer data through sales and service applications. Suddenly marketers everywhere were armed with the newfound capability to target customers more precisely, knowing where they lived, what they liked to buy, how often they bought, and their socio-demographic profile, extracted from large compiled consumer databases. As companies began to recognize the disproportionate value of repeat customers, thanks to customer information systems, the concept of relationship marketing gradually evolved into a management ideology.

A Visible Beacon

Just as all this was going on there was a powerful reform movement happening in the parallel universe of branding. Up until the 1990s branding was strictly a creative exercise, used to distinguish one product from another: a name, a logo, a tagline, a value proposition, a “how are we different” statement. But there was a growing appreciation that a brand was much more than the public face of a product: it had inherent equity – a value that went far beyond the sales numbers. There was stored value in the ability of a brand to command a price premium – in the current and future loyalty of its customers – in the consumer confidence it evoked – in its cultural impact. A brand could, in fact, become a “North Star” symbolizing the vision and values of the company.

Brand building was critical, not just because it created product awareness, but because it was the key to business coherence and sustainability

Brand building was critical, not just because it created product awareness, but because it was the key to business coherence and sustainability. Without a strong brand vision to keep it honest, a business could easily drift off course, unsure of the right direction to take. Strategic branding became a way to create an intangible asset worth far more than the balance sheet or share price might suggest – a visible beacon for all stakeholders: customers, employees, owners, and investors.

The End of Business As Usual

Apart from the emergence of customer databases in the 1990s, and fresh thinking around the meaning of a brand, marketing orthodoxy had not yet been seriously challenged. That began to change in the early dotcom years (1994-2001) when the seeds of marketing anarchy were laid.

As a first wave of opportunists sought to commercialize the Internet, every business began scrambling to put up a web site or launch an e-commerce storefront. By the end of the 1990s a rebellious wave of “digital utopians” had begun to promote the revolutionary potential of the medium, exuberantly declaring an end to “business as usual”. The Web was not just another channel to sell stuff, they preached, “it is a place where we humans get to talk with one another in our own voices about what matters to us” (The Cluetrain Manifesto, 2001).

As web design evolved from static to dynamic page building through the early 2000s, the idea of a true “market conversation” became feasible. The ensuing spread of social networking sites, blogs, review sites and user forums set in motion a dramatic shift in power from brands to a more connected and savvier consumer population. The abruptness of this change left most marketers frozen in time, their web sites still resembling “brochureware”. An aversion to risk stifled their creative use of social media: a branded Facebook page became a sanitized bulletin board instead of a vibrant brand community.

As the realization sunk in that the Social Web had snatched control of the brand away from them, marketers began to favour the concept of customer management as the most viable way to build long-term relationships. Traditional transaction-based loyalty programs were flimsy “barriers to exit”, creating a false sense of security. What was more important was creating an emotional connection to the brand. Something that would give customers a reason to believe in the brand beyond the product. Instead of pumping up the volume on paid media, brands needed to grow through “word of mouth” (earned media), capitalizing on the goodwill and advocacy of existing customers. The goal was to build customer equity – a predictable stream of assured revenue based on securing the brand commitment of customers – also known as lifetime value, a financial formula cribbed from direct marketing. The epitome of commitment: a willingness to buy regardless of enticements to switch.

True Engagement

The arrival of the iPhone in 2007 changed the digital landscape dramatically, igniting the mobile revolution. Many people were now living digital lives. Time spent on the Internet began to eclipse TV viewing. The path to purchase became asymmetrical. The buying funnel was no longer recognizable: more like a maze, resistant to “shock and awe” campaigning. Where do you aim your media artillery when your target population is spread out everywhere? When buyers can spring into view, anywhere and anytime, ready to buy? Battling over share of voice was no longer a sensible strategy – or very affordable. Not when the “voice of the customer” trumped brand messaging. As mass audiences began to drift away from print publications and “appointment” TV viewing, opting instead for streaming video and social media feeds as their sources of content and entertainment, budgets began to “follow the money” online where customers were now spending most of their screen time, much of it on their phone, texting and scrolling.

To just get noticed, never mind encroach on people’s time, brands needed to find a natural entry point into the lives of customers – a reason to initiate the conversation.

Brands were suddenly naked, no longer able to hide behind their “advertised specials” in the face of price transparency. And just being “good enough” sentenced a brand to market anonymity, making it a low-cost supplier. To just get noticed, never mind encroach on people’s time, brands needed to find a natural entry point into the lives of customers – a reason to initiate the conversation. Simply boasting about the functional benefits merely earned a brand the right to be considered, not short-listed. True engagement meant giving people a sense of belonging to something bigger than themselves – becoming integral to their lives in some way, culturally, socially or functionally. And that meant marketers had to define a clear brand purpose – a reason for existence beyond making a profit – fully aligned with the worldview of their core customers.

Turning Point

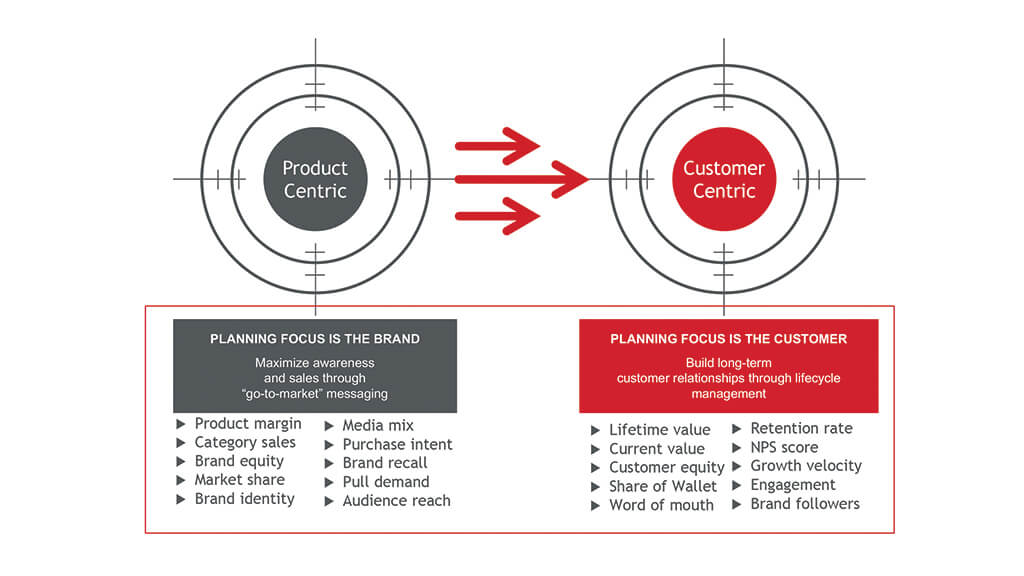

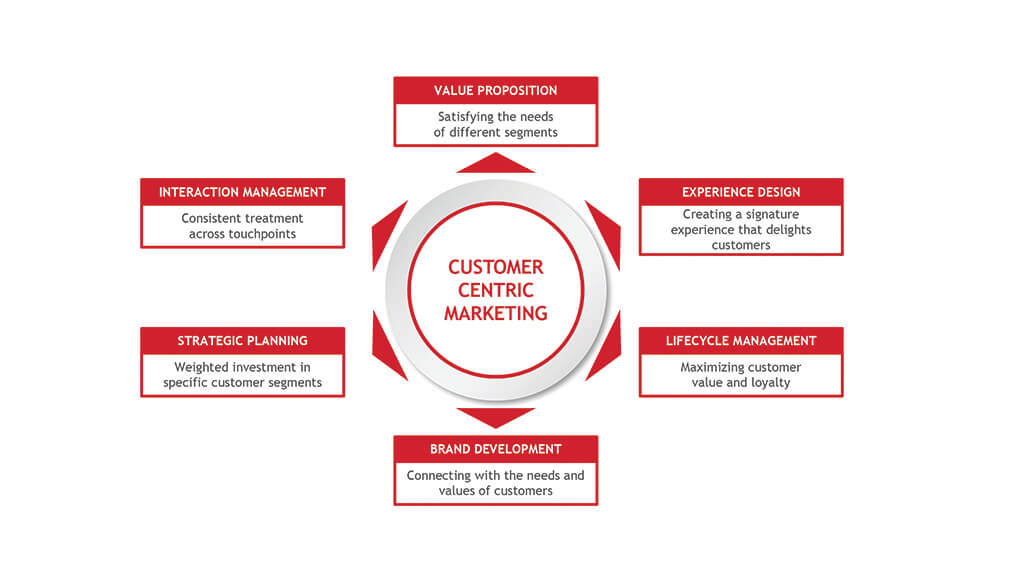

As P&G’s Mark Pritchard acknowledged, marketing is at a turning point, in desperate need of a “one to one” planning model that will be more customer-centric. While digital transformation is deservedly at the top of the corporate agenda, simply because of a growing mismatch between people’s expectations and their actual online experience, marketers know that it will take more than digital technology to make a difference. The new competitive battleground: making it as easy as possible for customers to interact across all channels, giving them what they need, at the time they need it, in the context of the moment. The catch, of course, is that there are so many more ways for people to connect today, using their PCs, tablets, smartphones, home appliances, even their digital watches. Designing a unified experience – never mind a memorable one – puts huge stress on the internal workings of companies which remain siloed in their thinking, devoid of a single view of the customer, held back by the glacial pace at which IT moves, and suffering from a corporate obsession with quarterly returns.

Brands need to escape the gladiator ring and find a higher order expression of the value they create

The front end of marketing planning – namely, segment identification, value proposition development, product innovation, demand forecasting – will remain the strategic pistons that keep the production lines humming. But the “go to market” end of marketing – from brand identity development to advertising and promotion to communications planning – is crying out for reinvention. Today people are more resistant to advertising than ever – more likely to buy on the advice of their social connections – more knowledgeable about their options – and insistent on a fair deal. The shopping malls are empty for a reason: people can find what they want instantly, at an acceptable price point, starting with a Google or Amazon search – and they are conditioned to expect delivery the next day. Latency has been stripped almost completely from the buying journey. Competing online has become a slugging match. Brands need to escape the gladiator ring and find a higher order expression of the value they create.

Brand Trust

Value creation is at the heart of the new marketing model – along with having a distinct social purpose. Nike’s bold new rallying cry, “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything” is an inspirational lesson for brand marketers everywhere: take a stand – in order to stand out. People prefer brands which have an authentic and meaningful credo that resonates with them. Social activism is now a tie-breaker.

People prefer brands which have an authentic and meaningful credo that resonates with them. Social activism is now a tie-breaker.

If a brand is truly close to its customers – understands their values and what matters to them – as Nike does with its millennial audience of aspiring athletes, as Patagonia does with its outdoor enthusiasts, as Unilever does with the women who love their beauty products, as USAA does with its extended family of military members – there is almost no down side to embarking on a social crusade. People today distrust corporate double-speak. They are troubled by corporations dodging their societal responsibilities (witness the rise of the “gig economy”) which is why brand trust has become the purest test of reputational strength. Marketing must lead the way in “humanizing” the corporation by making the well-being of customers (and society in general) a prime directive, as Philip Kotler, the “Father of Modern Marketing”, urges.

That’s how Amazon grew into a commercial leviathan: by being customer obsessed. According to its founder Jeff Bezos: “We’ve had three big ideas at Amazon that we’ve stuck with for 18 years, and they’re the reason we’re successful: Put the customer first. Invent. And be patient.” Jeff Bezos may be viewed by his competitors as Lex Luthor – but he is a hero in the eyes of everyday shoppers who only care about making life easier, more convenient and enjoyable.

Road to Reinvention

According to Forrester Research, “customer-obsessed” companies have the highest revenue growth – the highest customer satisfaction – the highest employee satisfaction. They’re at the top of the Net Promoter Score leaderboard. That reservoir of customer goodwill – earned by keeping promises, not making them – is far more sustainable than advertising can ever hope to achieve.

The old marketing model rarely thought about what happened after the sale. Marketing always figured their job was done at the sound of the cash register. Yet Amazon would never have succeeded if Jeff Bezos treated his first orders as just orders. He was creating lifetime customers. And that was his vision way back in 1994.

Getting the experience right in an omnichannel world is hard work. It takes a commitment to eliminate the pain points. To rewire processes. To understand what customers want and how they feel each step of the journey. It takes attention to detail. And it takes the courage and fortitude to flatten operational barriers, overcome rearguard resistance and debunk corporate shibboleths. That job belongs to marketing, not customer service. Because marketing should be solely responsible for managing the end-to-end relationship. Otherwise no one is accountable.

For that reason, the new marketing model must be organized around the successive stages of the customer lifecycle, from initial product discovery and brand exploration to continuous engagement. Repeat customers are won or lost by the quality and sincerity of their treatment over time. No matter where and when an interaction occurs, the experience should be seamless, personalized and relevant. By never confusing messaging with conversations – by delivering value with every interaction – by providing personalized treatment based on relationship history – by complying with the wishes of customers – brands can create a signature experience customer will want to talk about and share.

Done right, a reciprocal relationship encourages an unfiltered conversation ripe with possibilities. Marketers just need to tattoo themselves with a single motto: “Always Do the Right Thing”.

Finally, the old marketing model was never truly rooted in an understanding of customers because it lacked the tools to make insight a proprietary advantage. Marketers are playing catch up today, trying to connect their engagement platforms with systems of insight. Giving customers a compelling reason to reveal their true selves – to share their aspirations and goals – to talk about what matters to them – is the first step on the road to reinvention. It becomes the start of a reciprocal relationship where the conversation is enriched by knowledge of prior interactions and not guesswork – where customers never have to re-introduce themselves – never have to endure advertising messages masquerading as content – never have to “unsubscribe” in order to escape a promotional barrage – never have to scale a wall of apathy in order to get a compliant resolved. Done right, a reciprocal relationship encourages an unfiltered conversation ripe with possibilities. Marketers just need to tattoo themselves with a single motto: “Always Do the Right Thing”.

The biggest marketing challenge today is not coping with channel complexity: It is the shift in mindset from the brand as the focus of strategic attention to putting the customer at the centre of all thinking. A new “customer first” planning model organized around the relationship lifecycle is the answer. But getting that right will take much more than a simple three-page memo.

Stephen Shaw is the chief strategy officer of Kenna, a marketing solutions provider specializing in customer experience management. He is also the host of a regular podcast called Customer First Thinking. Stephen can be reached via e-mail at sshaw@kenna.ca